EAST PORTERVILLE, California – When her well went dry in 2014, Yolanda Serrato had just begun the fight of her life against breast cancer. Her world had already been turned upside down – then it went sideways.

Through chemotherapy and radiation, she often carried buckets of water from a 300-gallon tank outside so she could cook food for her family. She heated water on the stove for sponge baths. She even needed a bucket of water to use the toilet.

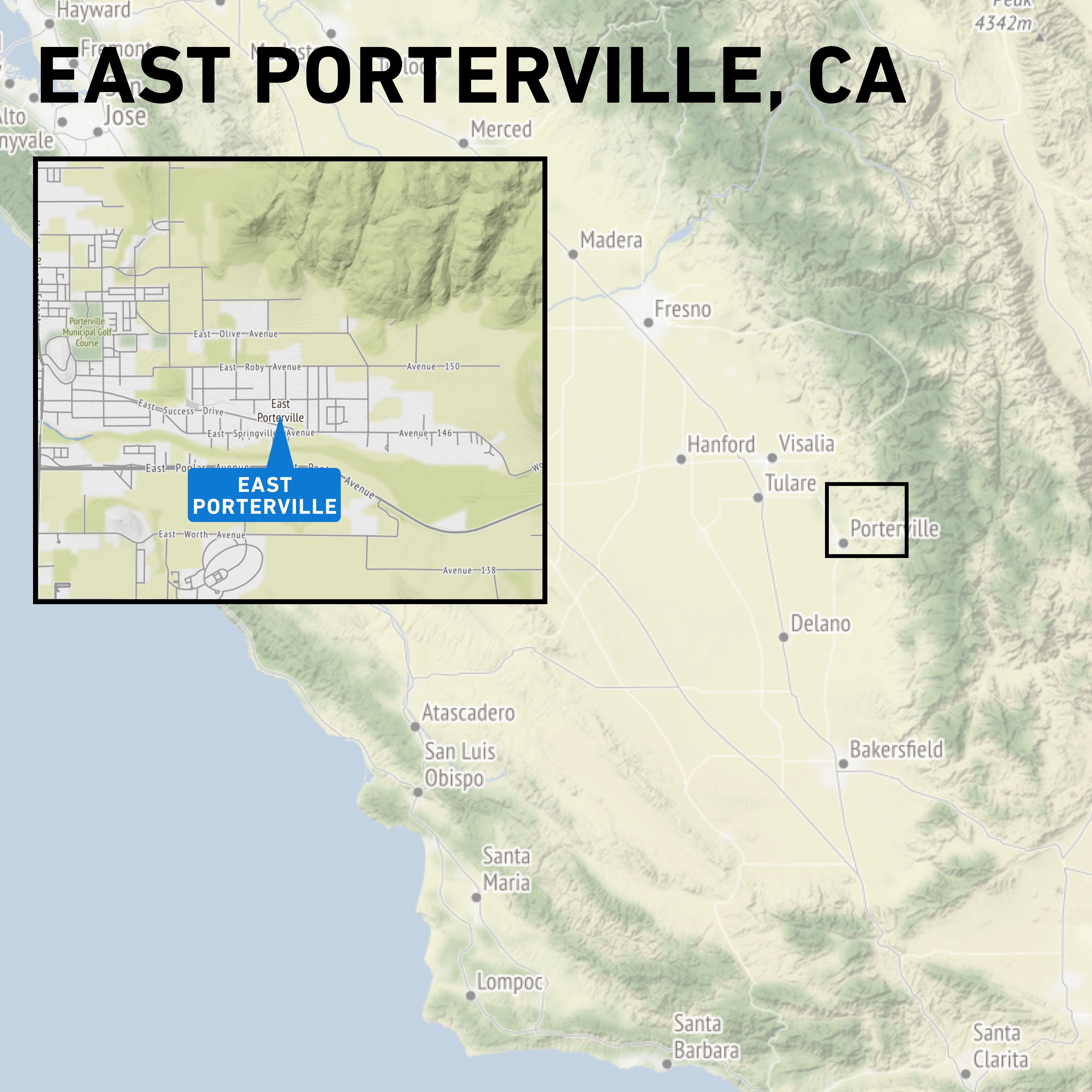

“I thought it was the end for me – it was exhausting,” says Serrato, 58, who has lived in an East Porterville house in California’s San Joaquin Valley for 23 years with her husband and three children, two of whom are grown. “You want to know what it’s like to live without water? Turn off your water for a week. That’s the only way you will know.”

Life is still upside down for Serrato, whose cancer has moved into her bones. But her house is now connected to nearby Porterville’s water system, not a dry well. Porterville has a water system that serves 60,000 residents with deeper community wells that survived California’s five-year drought.

More than 300 other homes in East Porterville, which has a population of 7,300, have already received the same long-term fix, some after living two years without functioning indoor plumbing. About 1,000 people – who live on 330 of the 1,800 properties in town – were without water at the height of the drought.

Indoor taps in kitchens, showers, bathrooms, washing machines and toilets just stopped working. Lawns turned brown, roses died, trees withered and dust collected everywhere. People scrambled daily to get water from relatives, friends and neighbors to get kids off to school and themselves off to work – many going to the farm fields in the vast agricultural belt of the valley.

Yolanda Serrato, then 54, and her family of five were reliant on water from this tank in front of her house in East Porterville when this picture was taken in Sept. 2014. Serrato’s well had dried up that year, during California’s drought, but her house has now been connected to Porterville’s water system by a distribution line. (AP/Scott Smith)

“I shudder when I think of getting up at 3 a.m. to get a bucket of water for my husband when he’s getting ready to go to work,” Serrato says.

East Porterville took by far the hardest hit in the valley during the drought, state officials say. And the valley suffered most in the state from the drought.

Volunteers, nonprofit groups and good neighbors eased the blow here by helping people find temporary water supplies. This rural community at the edge of the Sierra Nevada foothills pulled together. Now East Porterville is the biggest post-drought success story in this 25,000-square-mile valley.

But it came at a price. The State Water Resources Control Board has responded with $35 million to connect East Porterville’s 300-plus dry homes to Porterville’s system. Another 400 homeowners who didn’t lose their wells have opted into the Porterville hookup to prevent future water problems.

At one point during the drought, the state was paying $650,000 a month just for emergency water, temporary holding tanks and deliveries. The total cost of East Porterville’s drought rescue has been estimated at nearly $40 million. Authorities had little choice once they learned the extent of the suffering in East Porterville, state officials say.

“The East Porterville project is massive,” says Dat Tran, the State Water Resources Control Board chief of Drinking Water Technical Assistance. “As far as drought impact, this is the biggest project we’ve done.”

The state favors consolidating smaller, more vulnerable towns with nearby cities, so this may not be the last time California is on the hook for tens of millions of dollars. The valley has hundreds of rural pockets with water supply and contamination problems that have been festering for many years.

“The water and wastewater infrastructure costs that we’ve neglected over the past 30 years or so are not going to be cheap to fund,” says Michelle Wilde Anderson, a professor at Stanford Law School. “The longer we delay the costs of maintenance and new projects, the more we always pay when we finally face our basic needs.”

For now, the East Porterville fix has been moving quickly, with the installation of main lines, new wells and home hookups. The goal is to bring nearly half the town’s 1,800 homes onto the system serving Porterville.

“I’ve been in government a long time, but I’ve never seen a project of this scale put together so quickly,” says Eric Coyne, Tulare County deputy administrator of economic development.

At the same time, the drought left an indelible mark on the people, more than 70 percent of whom are Hispanic. It created a horrendous ordeal, says Tomas Garcia, who has lived in East Porterville since the mid-1990s. Garcia’s well went dry in 2014.

“We never knew our well was something to worry about,” says Garcia, 54, who eventually volunteered with nonprofit groups to help his fellow residents. “In the beginning, it was very hard. You had to find water and get it to your house. I worked such long days. I have diabetes. Now, I’m hooked up to the city of Porterville, but I still save water all the time. All the time.”

He says his monthly water bill is about $54, and he does not object to paying it, especially after he looked at the cost of replacing his old well.

A well-drilling contractor estimated the cost of a 200ft well would have been $55,000, Garcia says. Garcia’s wife, Juanita, works in the fields. He works for a tire shop in Porterville. They can get by as they raise their two children, but they couldn’t afford a new well.

Residents here are poorer than 91 percent of other Californians, according to the latest CalEnviroScreen data from the state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment.

CalEnviroScreen, which details stress in communities, shows East Porterville’s population is among the 5 percent of California residents who live with the most environmental, social and economic burdens. Factors include air pollution, poor water quality, low birth weight, issues of access to healthcare and language barriers.

The town’s drinking water source has always been shallow, private wells, some of which were dug down only 20ft by hand a century ago. The wells are not monitored by the state for contamination. In California, private well owners must hire their own contractors to test wells.

East Porterville’s geographic location is the main reason the wells are shallow. At the edge of the foothills just downhill of Success Lake, the soil below the surface is shallow because the granite base of the mountain range slopes upward. There isn’t as much room for underground water as locations farther west in the valley.

“The underground aquifer is more reliable where the sediments are deeper – as they are around Porterville,” says engineer Richard Schafer, watermaster for the Tule River Water Association, which manages water operations on nearby Success Lake. “For shallow areas, like East Porterville, there isn’t as much water, and it is recharged by the Tule. Remember, 2014 and 2015 were the driest seasons in 130 years on the Tule.”

Resident Donna Johnson distributes donated drinking water to East Portervillle households in February 2015. The cost of drought relief for East Porterville has been estimated at nearly $40 million. (David McNew/Getty Images/AFP)

Even though last winter was wet, there are still water supply problems in East Porterville, says Jessi Snyder of Visalia-based Self-Help Enterprises, which has worked with low-income families to build sustainable communities since 1965. The nonprofit has been a valuable resource for residents, helping them connect with the Porterville system or find financing if they need a new well.

“We’re still getting reports of new dry wells,” she says. “That’s why it’s important to have long-term solutions.”

There are a small number of properties still dry – a precise tally is difficult to estimate, officials say – but most places that lost water during the drought are now connected to Porterville’s system.

Ryan Jensen of the Community Water Center, which kept people informed and helped organize involvement in the hookup project with Porterville, says the entire process of fixing water problems here is focused on solutions.

“It’s a model that I’m hoping to see more and more,” he says. “We will have between 700 and 800 houses connected to the Porterville water system maybe by the end of the year. That’s impressive.”

Out in the community, stacks of bottled water still clutter some porches. Sometimes the garbage bins are filled with paper plates because people don’t want to waste water washing ceramic plates. It still looks like a community on the mend.

Fred Beltran, 62, a nearby Terra Bella resident who once lived in East Porterville, volunteered to work on water drives in East Porterville – getting donated water and delivering it. He had been in early retirement for a few years before the drought, but now he works for Self-Help Enterprises.

“Those water drives helped us understand what people needed,” Beltran says. “People didn’t have water to flush their toilets and take showers. We got them water tanks and connected them to the house plumbing and the hot-water heater. This was a devastating time but we pulled together.”

Yolanda Serrato, who continues to battle cancer, says she didn’t think of leaving East Porterville. She says she couldn’t have sold her house anyway after the well went dry. But she loves the quiet country life here. She says she’s staying.

Plus, the drought taught her children a few lessons about survival. The younger folks often worried how long anyone could live without running water in the house.

“I told them, ‘Yes, you can do it,’” she says. “We didn’t have indoor plumbing when I lived in Sonora, Mexico. You got a bucket of water to bathe and a cup of water to brush your teeth. But I understand why they’re afraid. You never know how precious water is until it’s gone.”