California’s water year officially began in October, and it got off to a good start, with above-average precipitation in Northern California. And then in January, things got even wetter as a series of heavily moisture-laden storms known as atmospheric rivers struck the state, delivering heaps of snow and rain.

Mudslides, flooding and raging rivers resulted as California’s reservoirs began to refill and the snowpack accumulated foot by foot in the Sierra Nevada.

After more than five years of drought, what does this mean for California? Is the state finally out of the woods?

1. Officially the drought is not over

While many news stories reporting on recent storms in California have declared California’s drought over, officially it is not – the decision to declare that falls to the governor, who announced a Drought State of Emergency on January 17, 2014.

“The governor has not declared it over – there’s a complicated number of factors that go into that,” said Doug Carlson of the California Department of Water Resources (DWR). That includes the amount of water accumulating in the snowpack, the amount of water in reservoirs and the health of groundwater, he said.

Although Northern California is looking good, serious drought impacts are still being felt in other parts of the state, particularly in Santa Barbara County and Tulare County.

“We say generally that as long as there are drought impacts being felt anywhere, you have to consider the drought is still underway,” he said. “It may not be as dire as it was two years ago. It’s looking much better than that this year for sure. But it could stop raining and snowing today and that would be it throughout the rest of the wet season. It’s pretty premature in January to make any kind of estimation about whether we are out of the drought.”

2. The area of drought is shrinking

The U.S. Drought Monitor’s most recently updated figures show changes in the area of drought. Right now 58 percent of the state is experiencing some level of drought, down from 97 percent this time last year and 81 percent just three months ago.

The Drought Monitor, updated weekly, shows areas and severity of drought in California as of January, 17, 2017. (U.S. Drought Monitor)

Most significantly, this time last year 43 percent of the state was designated as being in “exceptional drought” – the most severe drought designation. It included large swathes of the San Joaquin Valley, the most productive farming area for the state. But now that number has fallen to just over 2 percent of the state, concentrated in the Santa Barbara County area.

Large portions of the San Joaquin Valley and the Los Angeles area do still remain under “extreme drought,” a slightly less severe designation.

3. It’s raining and snowing a lot

Numbers tracking the amount of rain and snow across the state give reason for optimism, though.

Most major reservoirs across the state are doing well. Shasta is at 124 percent of the average for this time of year and 82 percent of capacity. Oroville is 126 percent of average and 81 percent of capacity. Don Pedro is 133 percent of average and 90 percent of capacity. Of the largest reservoirs, New Melones is the lowest, at 66 percent of average and 39 percent of capacity. Of biggest concern though is Cachuma reservoir, the largest reservoir serving Santa Barbara County; that is at 11 percent of capacity.

Rain and snow for the Sierra Nevada both look good. At the time of writing, the Northern Sierra precipitation index shows 217 percent of normal for this time of year, the San Joaquin region is 228 percent of normal for this time of year and the Tulare Basin is 230 percent of normal.

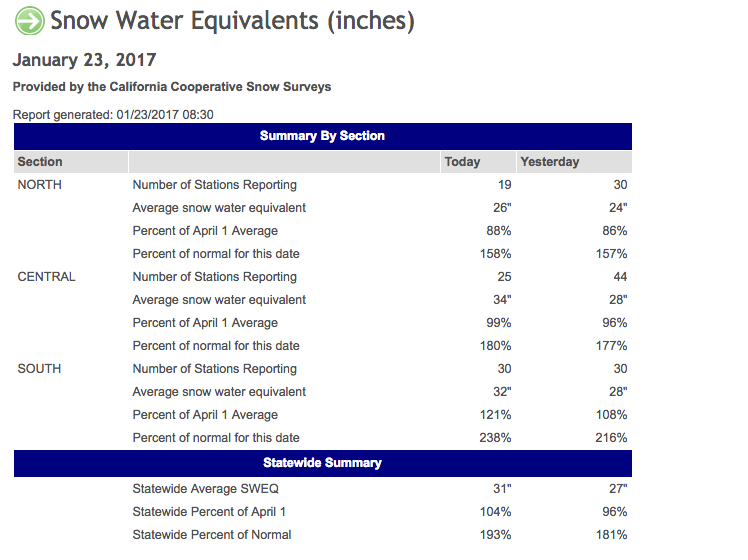

As of January 23, the snow water equivalents in the Sierra are 193 percent of average for this time of year and 104 percent of the April 1 average. Although a key to a robust water year will be making sure that warm temperatures do not prematurely melt the snow before it’s needed in late spring and summer.

The most recent figures from the California Cooperative Snow Surveys show that statewide the snow water equivalent is 193 percent of normal for this time of year. (Calif. Dept. of Water Resources)

4. Groundwater still a problem

One of California’s biggest problems is groundwater overpumping – something that won’t be solved in a single year. Recent rains can help aquifers, but it won’t happen immediately, because it takes a while for water to infiltrate underground.

In areas where groundwater is vastly overdrawn, it will take more than just rain, but also investments in water management that includes “conservation, stormwater capture, recycling, desalination, water transfers, diversion, conveyance and storage,” said Lauren Bisnett, an information officer for DWR’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Program.“Groundwater challenges, such as land subsidence, water quality and seawater intrusion have been decades in the making and it will take more than a few storms to alleviate these issues and bring basins into sustainable balance.”

California is working on a long-term strategy for making groundwater management more sustainable, which includes implementation of the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, but it will be decades before it is fully in effect across the state.

“Whatever happens this winter, the fact remains that California has been suffering through six years of drought – including the driest consecutive four years in state recorded history – and it would take more than the recent storms to turn that around,” she said.

5. Drought impacts will last for decades

A healthy snowpack and mostly full reservoirs bodes well for water being available this summer, but it doesn’t mean that all of California’s water problems are solved. U.C. Davis professor Jay Lund, director of the Center for Watershed Sciences, said that it will take decades for the state to recover from many of the drought’s impacts.

“Certainly the groundwater in the southern Central Valley (south of the Delta) will remain low in many areas for years or even decades. Dome groundwater in this region might never recover, as it is so dry down there,” said Lund. “Forest health impacts also could last for many years to decades – if a 30-year-old tree dies, it can take a long time to replace. Many of the depleted native fish were already struggling and could take a long time to recover.”

Similar sentiments were expressed in an opinion piece by Peter Gleick, president-emeritus and chief scientist of the water think tank the Pacific Institute.

“More than 100 million trees have died from drought, temperature stress and insect infestation,” Gleick wrote. “It will take decades for forests to regenerate, and the dead trees and damaged soils will pose forest fire and landslide risks for years.”

Gleick also added that salmon need not just water, but cold water, which means that lots of precipitation may not be enough. Ever. “Some urban or agricultural water users will never get all the water they want because formal water rights claims filed with the state are many times larger than California’s natural water availability,” Gleick wrote. “In this sense, some farmers are suffering permanent drought.”