In response to the migrant crisis, wealthy countries are preparing huge new development aid packages for many poor countries. The most likely effect of this aid will be to raise overall migration.

You read that right. The politicians who now promise to alleviate the migration crisis with development aid do not just speak without evidence, they speak against the evidence.

“I want to use our aid budget [for] creating jobs in poorer countries so as to reduce the pressure for mass migration to Europe,” says Britain’s Minister of International Development Priti Patel.

“To address the root causes of migration,” says Austria’s Minister for Foreign Affairs and Integration Sebastian Kurz, “we decided to double our direct bilateral development cooperation.”

A new half-billion-dollar aid partnership for Africa is explicitly linked to reducing migration pressure by driving economic development.

Development aid is a worthy policy in many settings on its own merits. It is responsible for some of humanity’s greatest achievements in public health and – to a limited degree – is capable of raising economic growth.

But the evidence we have suggests that development aid cannot reduce overall emigration from poor countries within our lifetimes – because in those countries, development itself goes hand-in-hand with greater migration. This is not to doubt that aid will work; the problem is that aid won’t reduce overall migration if it does work.

This is a stunner for many of my colleagues in development work. But half a century of social science has reached this conclusion. I review that research – from economics, sociology, demography, anthropology and geography – in a book chapter called, “Does Development Reduce Migration?”

First, the simple facts. Take a poor country, so poor that the annual income of the average person could only buy $1,000 to $2,000 worth of goods and services at U.S. prices. This includes Niger, Ethiopia and Mali. Now take a much richer middle-income country, where the same measure of average income is $7,000 to $8,000. This includes Morocco, El Salvador or the Philippines.

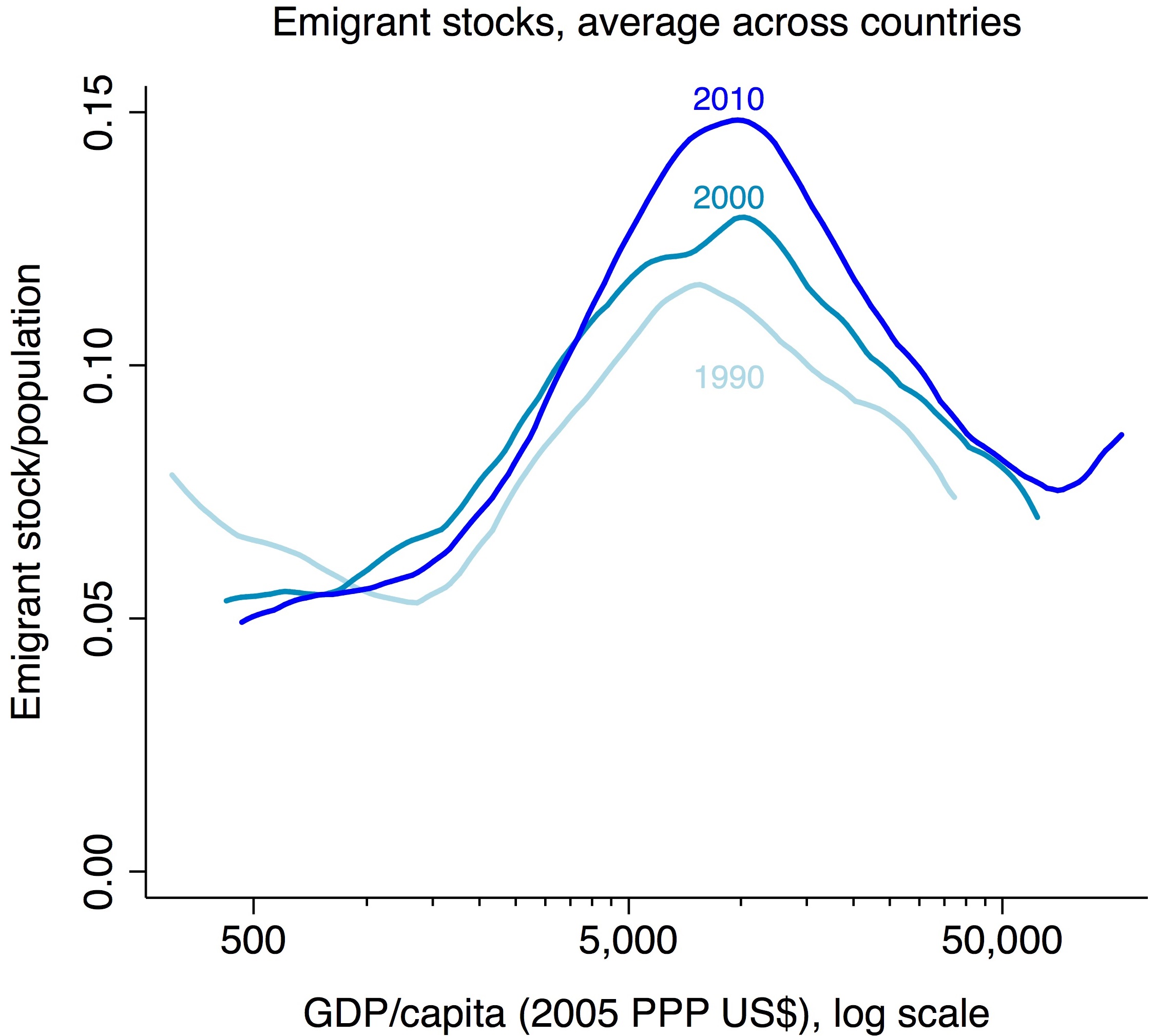

That richer group of countries doesn’t have a lower emigration rate, on average, than the first. Just the opposite: Those richer countries have three times the average emigration rate of the poorer countries. Here is how the average emigrant stock has varied with real income per capita over the last three decades:

Source: “Does Development Reduce Migration?”

Somewhere roughly around $7,000–$10,000 per capita, there is a turning point: Emigration from the average country starts to fall with greater economic development, as we might expect. Today’s poor countries are generations away from that level.

Why does emigration rise with development before that point? There are various reasons. Some relate to the fact that as poor countries develop, they tend to enter a demographic transition accompanied by a surge in the number of young adults, who are the most likely to migrate. And migration tends to snowball, as previous migrants assist the next wave. Recently released research by leading migration economists is starting to test the relative importance of these explanations.

But the most important reason is simple: For many of the poor, migration is an investment – an up-front cost for a large future benefit. And investment in migration rises as incomes rise for the same reason that other investments rise as incomes rise. With greater incomes, people have more resources to pay the direct costs of migration – transportation, documents, visa fees, smuggler fees.

And even more importantly, people with higher incomes get more education, which helps and encourages migration. Education directly assists migration because it lowers visa barriers and helps migrants get better jobs. And it encourages migration by giving young people a broader outlook, greater flexibility and higher aspirations.

Think about the calculation from the standpoint of a young man in Niger. If he stays home, he might expect to make $1,000 a year. If he makes it to Europe, he might earn $15,000 a year, a gain of $14,000 a year – the return on investing in migration. Suppose the economy develops very well in Niger, so well that average incomes double to $2,000 a year. The young man’s return on migration has barely changed: from $14,000 to $13,000 a year. But his ability to afford the investment is double what it was. He is more likely to invest than before incomes rose.

None of this relates to humanitarian aid, such as giving migrants basic shelter, food and health care. Such assistance can obviously stabilize migration flows in crises, and does little to raise overall purchasing power in a population of potential migrants. Jørgen Carling and Cathrine Talleraas find that the effects of humanitarian aid on mobility are complex and differ importantly from the effects of other types of assistance. Economists Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian have shown that some types of humanitarian aid tend to aggravate conflict, with possible implications for refugee flows.

All of this evidence suggests that rich-country policymakers have three broad choices as they respond to the migrant crisis. First, they can militarize borders and simply accept the dire consequences, which include 5,238 migrant deaths worldwide so far this year. Second, they can attempt to use development aid to reduce migration from poor countries, ignoring the decades of research showing that this will typically be ineffective at best.

Their third choice is to innovate. The world facing the migrant crisis desperately needs new institutions to shape international migration in ways that are more beneficial to the countries migrants arrive in, the countries they leave, and the migrants and their families. It needs visa systems that can respond to shocks rather than crack under pressure and feed black markets. It needs bilateral agreements to ensure that migrants acquire the skills that destination countries need. And it needs mechanisms to match those needs with skills that migrants already have.

But donors instead are simply pouring vast sums into border militarization and migration-deterrence aid. If they took just a sliver of that amount and invested it in developing new systems and institutions to make migration work better for everyone, they would address the real root causes of today’s crisis. And they would prepare for a future in which more migrant crises are guaranteed to come.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Refugees Deeply.