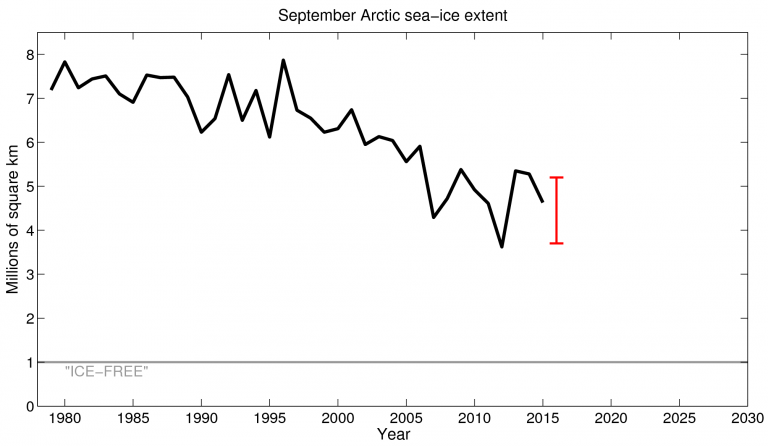

The melt of the summer sea ice in the Arctic is dramatic. Each September, when the ice reaches its annual minimum, there used to be around 7.5 million square km (2.9 million square miles) of ice. It is now regularly below 5 million sq km (1.9 million sq miles), and hit a record low of 3.6 million sq km (1.4 million sq miles) in 2012. This downward trend is projected to continue as global temperatures increase, but somewhat erratically.

The year at which the Arctic first becomes ‘ice-free’ (traditionally defined as 1 million sq km, or 386,000 sq miles) is much discussed by scientists and the media, but is often a controversial topic.

The IPCC AR5 assessed that the Arctic would likely be ‘reliably ice-free’ (more than five consecutive years below 1 million sq km, or 386,000 sq miles) by the mid-21st century, assuming high future emissions, but did not assess the year when it would first be ice-free, which would be earlier. Also, we have seen more ice melt than the models projected, so an even earlier date is a distinct possibility.

But, what about this year? I noticed this recent comment in the Guardian by Professor Peter Wadhams:

Most people expect this year will see a record low in the Arctic’s summer sea-ice cover.

However, the SIPN team, who collect sea-ice forecasts from 40 international groups, actually have none who think 2016 will be a record low.

Observations (black) and SIPN forecasts (red) of Arctic September sea ice extent. (Ed Hawkins)

In the Guardian, Professor Wadhams went on to say,

Next year or the year after that, I think it will be free of ice in summer and by that I mean the central Arctic will be ice-free. You will be able to cross over the North Pole by ship.

Professor Wadhams has made similar statements before – so should these forecasts be taken seriously?

Firstly, we should all make predictions ahead of time as this tests our physical understanding. Ideally, the methodology used should be clearly documented. The SIPN project described above has done this in a very open way and I have previously described informal efforts for Arctic sea ice forecasts.

Professor Wadhams also submitted a forecast to the SIPN team in June 2015 suggesting that the September ice extent would be 0.98 million sq km (378,000 sq miles), but has yet to publish his methodology, as far as I am aware.

In the end, there was 4.6 million sq km (1.8 million sq miles) of sea ice in September 2015, the fourth lowest on record.

Why does all this matter?

Such dramatic sea ice forecasts make headlines. They are shared widely around the world. But our credibility as climate scientists depends on communicating forecasts based on our best physical understanding. These forecasts may or may not change over time as more evidence accumulates. If we make predictions that turn out to be incorrect, then that should be acknowledged, the reasons understood and our understanding reevaluated.*

There are very serious risks from continued climatic changes and a melting Arctic, but we do not serve the public and policymakers well by exaggerating those risks. Journalists need to be aware of any past history of forecast successes or failures when writing articles.

We will soon see an ice-free summer in the Arctic, but there is a real danger of “crying wolf” and that does not help anyone.

Notes:

*Whether individual forecasts are “right” or “wrong” needs careful interpretation when considering probabilistic predictions.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Arctic Deeply.

This article first appeared on the Climate Lab Book, a blog written by climate scientists with the aim to promote collaboration through open scientific discussion.