In recent years, the media have paid close attention to the September predictions scientists make throughout the melt season. But it wasn’t always so.

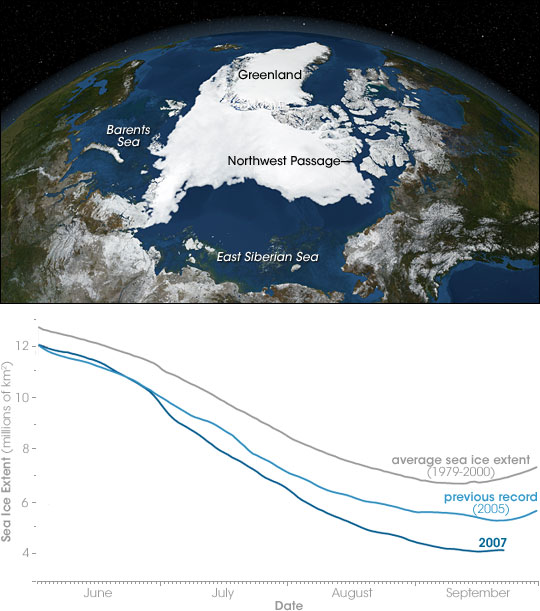

In September 2007, Arctic sea ice levels reached a dramatic and unexpected new low, tumbling to 4.154 million square kilometers (1.6 million square miles) – roughly 40 percent smaller than what it had been in the 1980s. Summer sea ice melt was far outpacing the models produced by scientists, prompting scientists to join together internationally to produce monthly reports on the anticipated state of the Arctic sea ice based on their individual assessments.

June through September 2007 brought record sea ice melt in the Arctic, well below the previous record low, set in September 2005. The image captures ice conditions at the end of the melt season. The summer of 2007 brought an ice-free opening though the Northwest Passage that lasted several weeks. (Arctic image courtesy NASA Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio. Graph courtesy Walt Meier, National Snow and Ice Data Center)

The Sea Ice Prediction Network (SIPN) was launched in 2008, releasing its first report on June 10 of that year. Then, as now, the predictions spanned a large range, some lower than the September 2007 minimum, some higher. But no one suggested the September sea ice extent would return to the 7 million square kilometers (2.7 million square miles) it maintained between 1978 and 2000.

Since that first report, the informal network has secured funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation and other agencies to transform what had been an informal operation into a more organized effort. “We wanted to see what we could do to improve sea ice forecasting,” says Julienne Stroeve, one of the network’s leaders and a climate scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. “It really shows that there is a lot of work that still needs to be done.”

Now, every May, a call goes out to those who are interested in the future of Arctic sea ice, asking them to begin preparing their predictions for the coming September. The reports are updated each month throughout the summer, folding in new data, such that by the end of August, the scientists – and citizen scientists – who get involved are basing their predictions for the September minimum on data from May, June and July.

The Sea Ice Outlook Report is not meant to be a formal forecast, but a tool that provides researchers with a better understanding about current condition of the sea ice and its evolution, so they can work to improve their methods. “Sea ice forecasting is quite a bit behind weather forecasting,” says Stroeve.

Many of the scientists who are part of SIPN produce their outputs based on highly sophisticated dynamic models of the sea ice, some of which take into account the interactions between the sea ice, the ocean and the atmosphere. But even these have tended to underestimate sea ice melt. The network can help scientists work out where those deficiencies lie. “Do we need better data on sea ice thickness, for example, or improve the way we model the physics of melting,” says Stroeve.

Other contributors base their predictions on statistics, including David Schroeder, a researcher at the University of Reading in England, who developed and manages the the sea ice model CICE at the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling.

Schroeder and his team have identified a correlation between the fraction of the sea ice covered by melt ponds in the spring and the ice extent in September. The ponds, which are puddles of water lying on top of the sea ice, are darker than the surrounding ice and absorb more heat from the sun, which causes the sea ice to melt more.

Melt ponds on the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean reflect less sunlight and increase warming and melting of the sea ice. (NASA/Kathryn Hansen)

Melt ponds begin forming in mid-May, says Schroeder. Typically, by the end of May, the melt ponds cover less than 1 percent of the sea ice. But by June it rises to 15 percent and by July the fraction hits 30 percent.

But that coverage is also influenced by the condition of the sea ice. “Very old sea ice is thick and rough, and the water tends to gather into the gaps between the ridges, so it covers a small area. But when the sea ice is young and flat, the melt ponds cover a large area, and the impact on albedo [reflected sunlight] is quite strong,” says Schroeder.

Scientists studying the age of the Arctic sea ice have found that it has become younger and thinner since the 1970s. In March, the NSIDC reported that 70 percent of the sea ice covering the Arctic Ocean had been formed in the past year and 30 percent consisted of multiyear ice. In the mid-1980s, most of the ice was at least two years old.

“As the melt season is changing and it starts earlier and goes longer, the melt pond is becoming more important,” says Stroeve. “If you develop them earlier in the season, then you are enhancing the melt. They’re probably playing a larger role than they did.”

Even so, the scientists know the output from their models may not always square with their own suspicions, illustrating the difficulties associated with making sea ice predictions. For July, Schroeder and his group submitted a report predicting sea ice extent would reach 5.2 million square kilometers (2 million square miles) in September, slightly higher than it was in 2015. “It’s the second highest in the July report,” he says. “But I wouldn’t say that this is what I believe it will be. I would expect that this is on the high side.”

Earlier this week Arctic sea ice reached 7.2 million square kilometers (2.8 million square miles) and – depending on which group of scientists you put confidence in – it could lose another 2 million square kilometers (0.8 million square miles) or shrink to half its current size over the next two months.

Tourism, shipping and natural resource extraction companies are all interested in advance predictions on the state of the summer sea ice. (Wikimedia/Gary Bembridge)

There is plenty of interest in sea ice extent throughout the summer beyond the rubbernecking. Companies involved in shipping, oil and gas extraction and tourism in the Arctic are all influenced by the location and thickness of the summer sea ice. Local communities could also benefit from the information.

“The problem is that people want these forecasts far in advance. They want to know in January how much ice there will be in September,” says Stroeve.

Stroeve says there is still a lot of work to be done by the sea ice community as a whole to improve scientists’ understanding of sea ice physics and the factors driving sea ice melt, as well as providing better regional forecasts.

Although there will always be interest in predicting the final summer sea ice extent, it’s the proximity of its limits to shipping routes, oil drilling rigs and communities that matter to the people living and working there.

David Schroeder and his group provided a prediction for this year’s September sea ice extent that is higher than it was in 2015, not lower, as indicated in an earlier version of this article.